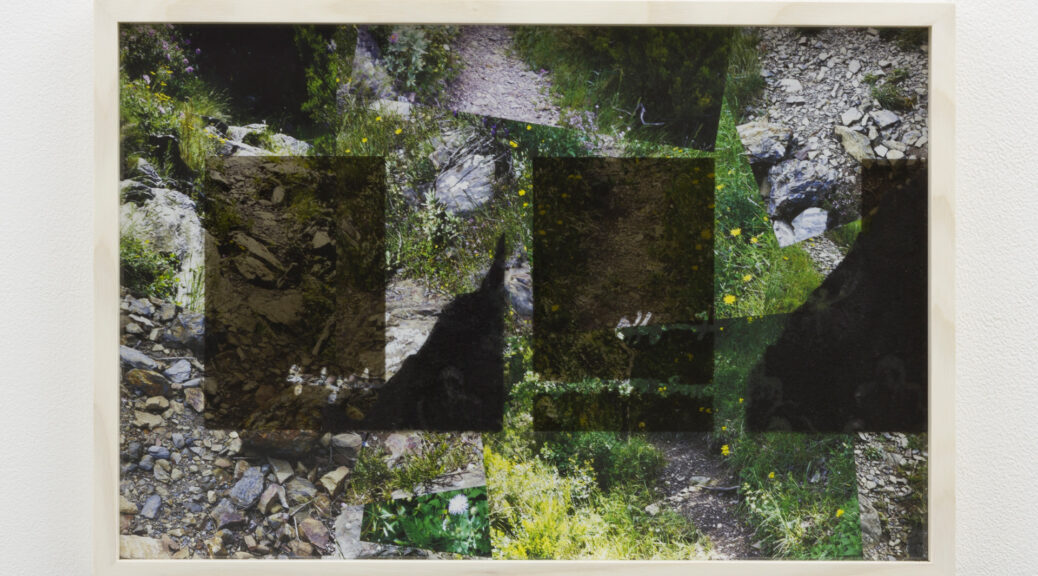

C-print, acrylic lacquer, charcoal, glass, 4 peaces, each 30 x 40 cm

Exhibition: Waitingroom, Tokyo (JP)

C-print, acrylic lacquer, charcoal, glass, 4 peaces, each 30 x 40 cm

Exhibition: Waitingroom, Tokyo (JP)

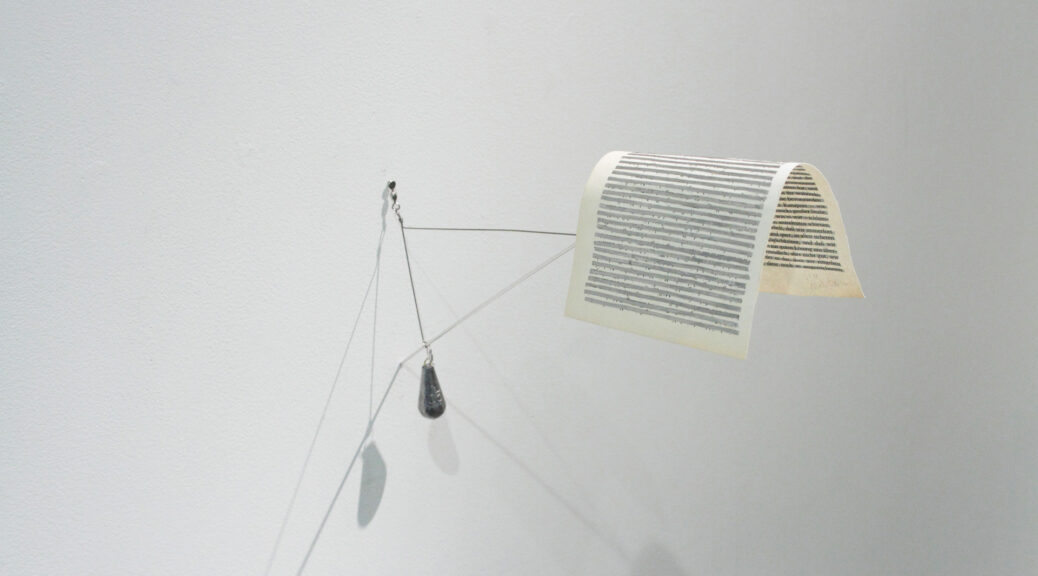

paper, nail

Photo: Kenichi Amano

There are territorial, geographical, biological, social, economic, moral, aesthetic, performance and decency limits.

In the work “Routes of Migratory” (2015), the silhouette made of coloured cardboard traces the flight routes of migratory birds, and in the work “Continent of Africa” (2015), all boundary lines are seen on the continent Africa. The colourful outlines are loosely hung on small needles, they could be exchanged, removed or replaced. They are fragile and provisional, endangered and changeable, too.

It is striking that the flight paths of the birds on their annual migrations from Africa to Europe and back draw flowing, round and playfully light lines. This makes it possible to associate the boundlessness of flight and any kind of footprint as utopia. The harmonious forms are a counterpart to the often jagged and sharp-edged appearing state boundaries on the southern continent, whose arbitrary drawings document the political drama of Africa.

Exhibtions: Ermkeilkaserne, Bonn (DE) / Frappant, Hamburg (DE) / Waitingroom, Tokyo (JP) / VOLTA 14, Basel (CH)

Image: Catalogue “DELIKATELINIEN”

Metal, mirror, string, plastic, paper, wood, LED, video (HD, 12’40 ),

photo (State Archive Hamburg 720-1 151-81= 17 131), wooden crate: 205 x 146 x 166 cm

The German-Jewish writer, Heinrich Heine, who lived in Paris in exile. Even the 1891 monument to him, ordered by the Austrian empress Sisi, was taken on an involuntary journey from Rome via Corfu to Hamburg, Marseille and Toulon. Heine’s monument was repeatedly set up in these various locations and then diminished, reviled, smeared, or damaged until it was finally hidden in a wooden crate (for 23 years long). “Wandermüde” is a mixed-media installation about the Odyssey of Heine´s sculptural monument. The video shows the currently view of the statue at the Botanic Gardens in Toulon (2014) and the process of the journey the statue.

Exhibition: Galerie im Marstall, Ahrensburg (DE)

Images: catalogue “DELIKATELINIEN” / catalogue “Von Wörtern und Räumen”

Video can tell any number of lies. And it can also unexpectedly capture the truth. Understanding this exposes the degree of uncertainty in what we see as well as the ambiguous nature of our perceptions and memories. In the work of Kawabe Naho, an artist who got his start in video, we are at times left with the sense that there is no boundary between truth and lies.

For example, in Kawabe’s 2004 video work Sugarhouse, the first thing we see is a completely white screen that does not seem to contain anything. But after red water is poured into the space, the forms that are actually there gradually become distinct. Just as we are beginning to grasp the complete picture, a house, made of sugar cubes, instantly dissolves into the red water. According to Kawabe, “Changing something invisible into something visible is a kind of vandalism and our gaze is fraught with the danger of altering the subject.” Here, Kawabe hints at the violent nature of a gaze, but when we consider why the things that collapsed were there in the first place, we realize that the work also casts doubt on the Japanese family system. Wash Your Blues (2007) is a four-minute video work depicting a polar bear at the zoo engaged in stereotypical animal behavior. Echoing the catchphrase for the American anti-depressant Prozac, “Wash Your Blues Away,” the work shows the bear constantly moving up and down as the surrounding pool of water is gradually bleached from blue to white. To the bear, the scene might resemble a fondly-remembered landscape. While the work suggests the dark side of a life-long education facility like a zoo, if we put ourselves in the bear’s place, the world might on the one hand seem dazzling after the blues (depression) have disappeared, but on the other hand, it might also seem empty and monotonous.

Kawabe’s works contain a mechanism that disturbs our sight and memory. This is not simply a trap that leaves us feeling bewildered, but something that is necessary in order to confront us and make us notice the bustling sensations that are concealed within ordinary life. Kawabe has skillfully employed this trick throughout her career, in her videos, installations, and art objects. For example, in the installation Cosmic But Unfair #2, shown at Shiseido Gallery in 2011, a device that deceives our eyes causes us to move back and forth between the invisible and visible. The approach is the same in both Kawabe’s works with and without a light source. For the 2012 work We Are the Strangers!, the artist cut out numerous mentions of the first-person pronoun “I” from an English edition of Albert Camus’ novel The Stranger and connected them together with string. Detached from context, all of these “I”s float freely. Though most of them probably refer to the novel’s protagonist Meursault, they inspire us to ponder the “I” and “we” as they relate to society with its occasionally changing aspects.

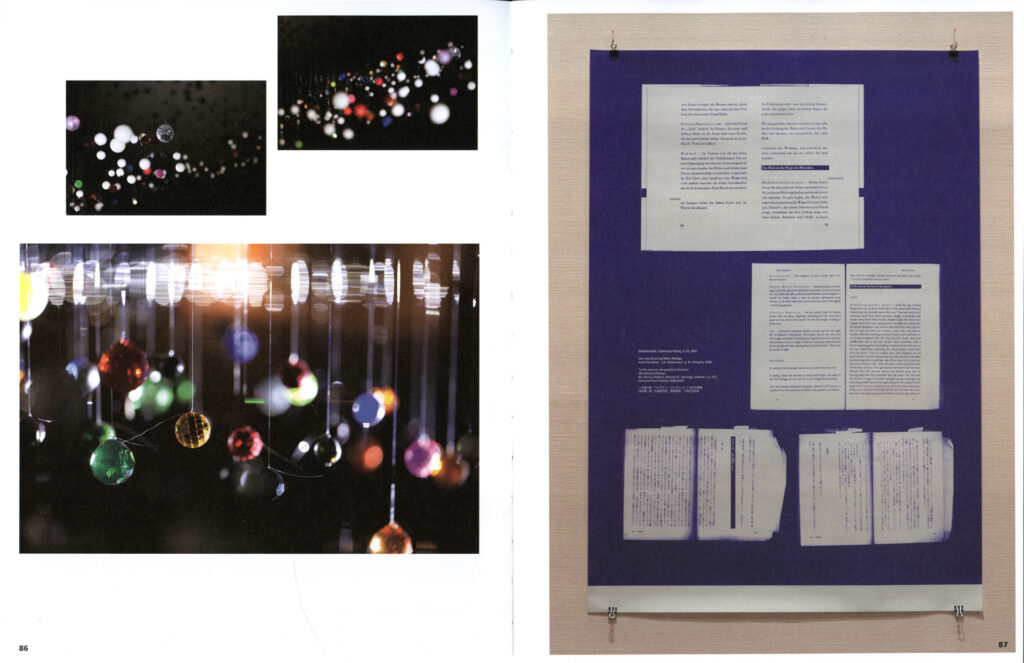

Glasses Shop, displayed in the museum’s poured-concrete storehouse, developed out of Kawabe’s use of spheres, which began in 2011. Various colors of small hanging orbs are lit with two spotlights. The orbs recall clouds, atomic structures, celestial bodies in space, or perhaps even human beings, and from only one direction, their shadows look like letters projected on the wall. Die Neige des Menschen (The Lees of the Person) refers to a phrase from Walter Benjamin’s One-way Street in which the writer compares gazes to human remains. This suggests our own experience of looking at the work as well as a cynical view of the human gaze, which can never be neutral in apprehending letters or perceiving shadows. Even when a person sees a language they do not know, they can identify the series of dots as writing. This raises questions about what distinguishes writing from non-writing. Though invisible, we recognize the existence of this “border” or “line,” which exists of its own accord. Kawabe shot his only video work in this exhibition, Pendule des Pyrénées (Pendulum of the Pyrenees), by setting up his camera near the border between Spanish and French Pyrenees, the mountains that Benjamin attempted to climb in order to cross the border into Spain at the end of his life. While there is no visible division or change in scenery between the two countries, the line had the power to obstruct people and completely change their lives. Other works such as Horizon Never Lurches, modeled on the form of a lace curtain and made with crushed charcoal dust, and Flowers and Borders also raise questions about borderlines.

Finally, Expurgation is a work made up of pages removed from various books in which letters and diagrams have been covered with tin tape. In light of recent events related to the threat of concealed information, which seems like a throwback to a previous era, Kawabe uses a physical technique to ask why writing that should exist has become invisible. The thin paper beneath the writing, sealed in metal, creates an added sense of weight and portent. Shining brightly in the strong light, the work pierces our eyes, asking what we can and cannot see, and who we are.

in: In Search of Critical Imagination, Fukuoka Art Museum, 2014

Page, zinc

Exhibtions: Fukuoka Art Museum, (JP) / Frappant, Hamburg (DE) / Port Gallery T, Osaka (JP) / VOLTA 14, Basel (CH) / Waitingroom, Tokyo (JP)

Images: Katalog “IN SEARCH OF CRITICAL IMAGINATION”

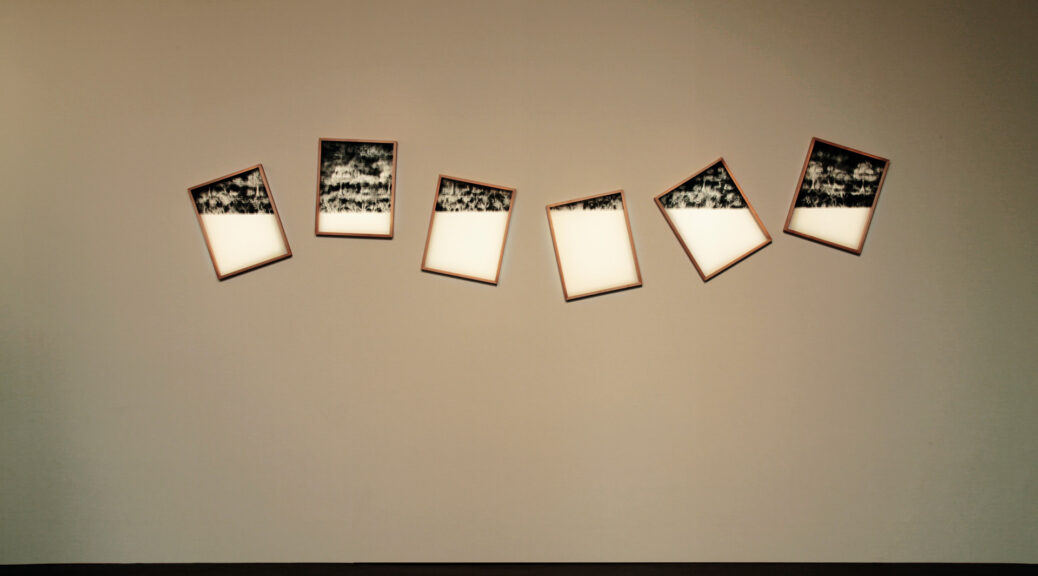

Charcoal, glass

Exhibtions: Fukuoka Art Museum, (JP) / Frappant, Hamburg (DE) / Take Maracke & Partner, Kiel (DE) / Schloß Agarthenburg, Agarthenburg (DE)

Images: Catalogue “In Search Of Critical Imagination“

Exhibtion: 8. Kunstfrühling, Bremen (DE)

Images: Catalogue “8. Kunstfrühling” / Catalogue “DELIKATELINIEN” / Book “Transitorisch”

2014

25,5 x 20 cm, 179 pages

Languages: EN, JP

Published by Fukuoka Art Museum

Text: Sachiko Shoji, Tessa Morris-Suzuki

Design: Shunsuke Onaka (Calamari Inc.)

Photo: Shintaro Yamanaka (Qsyum!)

This catalogue is published in conjunction with the exhibition „In Search of Critical Imagination“ at Fukuoka Art Museum 2014

Curated by Sachiko Shoji

Order here:

Fukuoka Art Museum (Fukuoka) , online store

NADiff (Tokio)

Metal, plastic, mirror, cardboard, glass, wood, motor, LED light, size variable

A swarm of spheres with different sizes, colors and material, floats in the space. More than 200 spheres made of blunt lead, reflecting glass, colorful plastic, are hanging with invisible threads from the ceiling and are irradiated by a moving spotlight. At first glance the sphere´s swarm looks like an unstructured cloud which keeps faintly moving by the breeze. The colorful swarm is illuminated by a spotlight, placed on a motor, which turns right and left like a searchlight so that the moving shades of the spheres form a sentence fragment on the wall. The sentence, “Die Neige des Menschen”, is a quotation from Walter Benjamin´s essay, “Einbahnstraße”, poem “Optiker” (1928)

Document of installation “Optiker” 2014 at Fukuoka Art Museum, Japan

1′ 09

Exhibtion: Fukuoka Art Museum, (JP)

Images: Katalog “IN SEARCH OF CRITICAL IMAGINATION”

(…)

As is generally known, the latest major natural disaster that took place in Japan was a tsunami, which even a nuclear power plant was unable to withstand. In March of 2012, Naho Kawabe photographed many damaged or extensively demolished single-unit houses in the prefecture Miyagi, which had been affected by the tsunami. Contrary to the classical viewer of ruins, without knowing how the buildings had fallen into this state, one would immediately ask for the reason for the destruction. Followed by the question regarding their fate: will these houses be repaired or torn down and replaced by new ones? The photos served for the preparation of a video film in which the camera positioned in a moving car slowly and steadily captures the remains of an almost totally destroyed small harbor town. Only a few solitary houses remain standing. The remnants of other houses have already been completely cleared away. Here, on the abandoned areas located between these, where beforehand the photographs had only depicted dust, sand, and litter lying around, a few months later numerous sprouting plants are visible. Water penetrates from the depths to the surface of the ground. Nature is retrieving the terrain that has become available again.

Naho Kawabe is interested in the partially subtle processes, the gradual changes that both physically and also temporally pose a contrast to the massive force of the catastrophe. And Kawabe captures that, which in only a few years might have entirely disappeared. Furthermore, with reference to the buildings, she does not place her focus upon representative, monumental constructions, but upon simple single-family houses and multi-dwelling units. For many architects, a vacant lot that can be newly cultivated has much fascination. (…)

But a new construction can also come across in such a manner that nothing remains recognizably visible of the past. In 2008, when celebrations of the 50th anniversary of its reconstruction were underway, Naho Kawabe visited the French beach resort Royan, which had been almost completely destroyed during the Second World War. The ambience of Royan, reminiscent of a kind of Disneyland, inspired Jacques Tati to create the movie Mon Oncle (1958), a satire on architectural Modernism and the absurdity of a technically totally engineered form of everyday life. The residential houses and hotels, which Naho Kawabe depicts in her photo series The Palms of Royan, indeed create the impression as if they were part of a gigantic film set. Furthermore, the absence of human beings creates the impression that the houses in question might not be true to size, but rather scaled-down models. This bears reference to the houses of Miyagi, which have also been photographed in such a manner that just from looking at them we are unable to discern whether they are showing authentic destruction or only the model of a simulation of tsunami damage.

Naho Kawabe shows us the world quasi in another aggregate state: not in its physical solidness, but rather in a transitory, ephemeral state, which also finds expression in her penchant for materials such as, for instance, coal dust. The ruin is not only an occasion to meditate about the past or transience as such, but rather an expression of transitoriness, of the transition from one state to another. It is not what remains in the eternal cycle of evanescence, but in itself something ephemeral that will disappear. Thus, Naho Kawabe continues to realize the motif of the house and the ruin time and again in ephemeral materials, such as, for example, in a panoramic coal drawing created in 2006 or in the short video Sugarhouse from 2004. Here, the house dissolves in a time span of four minutes. If the classical European ruin is a silhouette that stands out against the sky like a memorial, then the ruin, as it takes shape in the work of Naho Kawabe, is a fleeting trace, a calligraphic sign, which briefly appears and then disappears again, borne away like leaves in the wind.

in: Naho Kawabe. Observer Effect, Berlin 2013