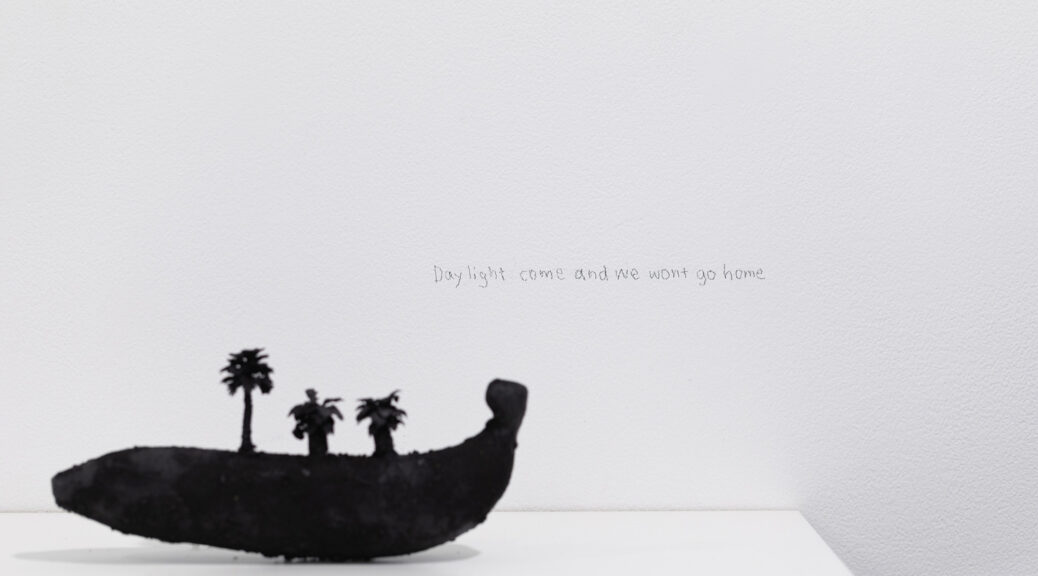

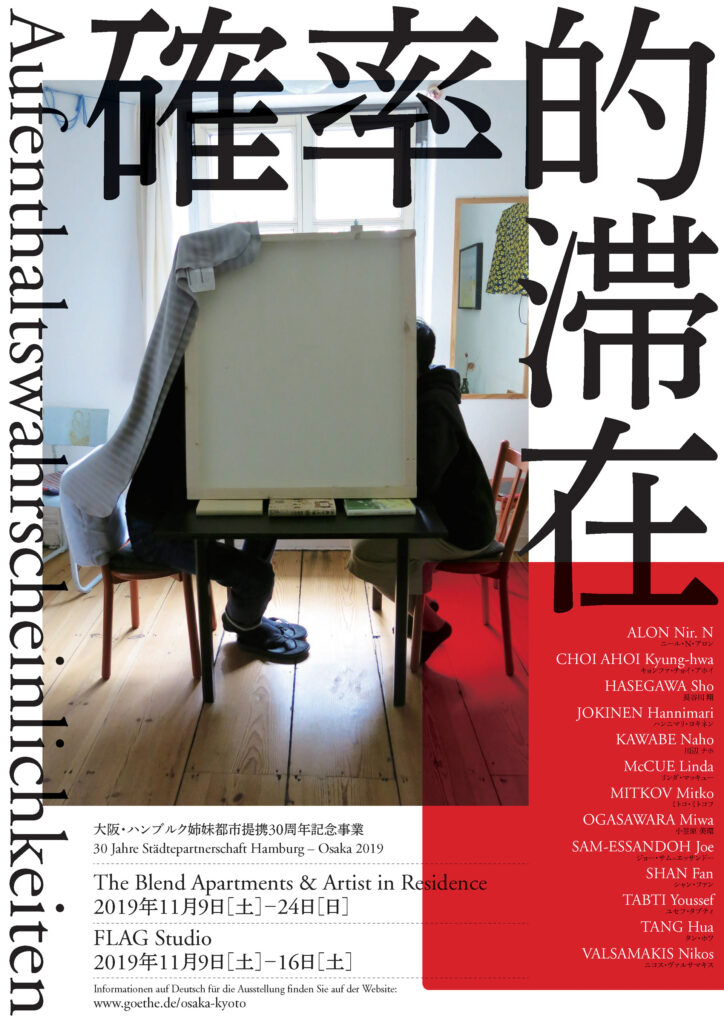

In the contemporary art scene, artists are expected to manifest the aesthetic and social context of their works. In view of my own situation, I am basically interested in the strategy that artists use to make themselves understood in a foreign language. Does linguistic reformulation change their works and their personalities? In a world that is growing together due to globalization, society is becoming increasingly attentive to cultural differences. Artists who live a far away from their own culture for a long time lose their affiliation to their culture and develop – figuratively speaking – a nested cultural identity. Does this condition effect on the behavior of artists and their artistic formulations? Based on these questions, I have chosen the title of the project “Aufenthaltswahrscheinlichkeiten (Probabilities of Residence)” and have integrated a surprising fact that there are very few foreign artists living in my home country, Japan, into the exhibition project at the same time. Based on my own experiences in Hamburg, I first developed a list of 25 questions that I wanted to ask artists from other countries living in the Hanseatic city and record as an interview. To be able to record their voices acoustically protected, I built a small mobile and quickly assembled box and used it to visit the artists in their studios. When I was in the studio of Joe Sam-Essandoh, he noticed my plastic carrier bag with which I transported the recording box and started to laugh: “Do you know what this kind of carrier bag is called? These bags can often be found in stacks, in different sizes but always with a typical check pattern, in the many small household or souvenir shops in Hamburg, which are mostly operated by Mediterranean traders. I got the bag from Claus Böhmler, a former professor at the University of Fine Arts of Hamburg as well as Fluxus artist, who developed a special interest in unusual everyday objects and collected them. He probably knew the significance of the bag – but for me it was only ideally suited for transporting large items at first. Before I met Joe, I didn’t know that it had a special name: The bag is called “Ghana must go”, since 1983, when the Nigerian president Shehu Shagari expelled over two million undocumented emigrants from his country. More than half of the emigrants originally came from Ghana and now returned home through Benin and Togo. They carried their belongings in the soft and stable carrier bags, which have been called “Ghana must go” worldwide since then and have even made it to a bestseller. When I travelled from studio to studio by Hamburg’s public transport in the summer of 2019 with this patterned bag for the project, it must have been a curious sight for passengers, especially for those who knew the story of “Ghana must go”: a slim Asian woman with a large bag on the way.

In this case, the bag is a plain object of daily use, at the same time, it projected different stories simultaneously. As a user of the bag, I realized that it has a wide-ranging significance for others as a transport tool. This allowed me to see my own situation as a Japanese woman in Hamburg from a new perspective. These everyday processes of exchange between people of different cultural backgrounds are deepening, changing and opening up my interest in the fates of initially strangers, who live in the same place I live in too – various worlds, perspectives and positions mix and overlap, almost like constantly forming new constellations. In quantum theory, it is assumed that the smallest particles constructing the world together, can be observed and determined, but they cannot be fixed because they are fleeting. In physics, the term “Aufenthaltswahrscheinlichkeiten” describes here and there, presence and absence at the same moment, stability and instability. Anyone with a temporary residence permit becomes restless before going to the “Aliens’ Office” to apply for a further residence permit. This raises the question: “What is the probability of getting an extension of residence permit?” If the physical world is based on probabilities, then only probabilities can be made about my fate. To put it in a nutshell: Can I stay, or do I have to pack my bags?

The artists participating in the project are from different countries and have developed very varied artistic positions. The works shown in Osaka were selected together with the artists. In the exhibition, I show a video, which is accompanied by a sound collage in German language from the interviews recorded in Hamburg. Simultaneously, the comments of the interviewees in the video can be read in Japanese script. These conversations in German between the artists and me are the talks by two person who was influenced by a different language culture background. The ambiguity that resulted from it turned into a fruitful exchange as stepping on each other. Should the exhibition concept – combining artworks, video, spoken and written language – contribute to understanding between the cultures and the twin cities, I would be delighted.